Taxes. Yawn. Right?

Wrong.

For many Canadians, taxes form the largest expense in their budget. And for many employee-Canadians (vs. self-employed Canadians), you’re going to pay close to whatever your company’s tax slip says you’re going to pay. And because tax is often withdrawn right from your paycheque, you might not even notice how much you’re actually paying.

Now, this is not a post slamming nor condoning our tax rates, nor is it a post on how to reduce your taxes. And I’m certainly not advocating for cheating on your taxes. Oh, and I’m also no tax expert, so take everything I say with a grain of salt.

So…

Why Should You Care?

It’s important to remember that accelerating your net worth is not about how much you make, it’s about how much you keep (and then invest). And getting ahead in life means balancing your time spent pursuing your passions with your time spent making money to afford those passions. In other words, it’s a giant optimization problem. So let’s figure out how to optimize it, or at least understand the implications of your choices so that you can be deliberate in how you spent your time and earn your money.

Getting ahead in life means balancing your time spent pursuing your passions with your time spent making money to afford those passions.

Also, if you’re considering contributing to your RRSP (Registered Retirement Savings Plan) or your TFSA (Tax Free Savings Account), you may wish to consider it in connection with your marginal tax rate in order to balance out the now-vs-later benefits of these programs. Perhaps I’ll write another post some day about RRSPs vs. TFSAs, but I certainly won’t be going into those details today.

Put another way, the reason why it’s important to consider your marginal tax rate when making an employment or investment decision is because it is directly connected to how much tax you will pay on that decision.

For example, if you’re in the 50% tax “bracket” and choose to take on a short-term second job earning $1000, then you’ll pay $500 in taxes on that new income. So you’re really only putting $500 in your pocket. By contrast, if you’re in a 25% tax bracket, you would only pay $250, keeping $750 in your pocket. And with that knowledge (combined with the rest of your personal circumstances), you can choose whether it’s worth your time to pursue that income.

What is a Tax Rate?

Simply put, a tax rate is how much tax you pay as a percentage of whatever is being taxed, as seen in the income tax example above. Similarly, a sales tax rate is obviously the percentage of tax you pay when you buy an item (your $30,000 car turns into $33,900 after adding in 13% sales tax).

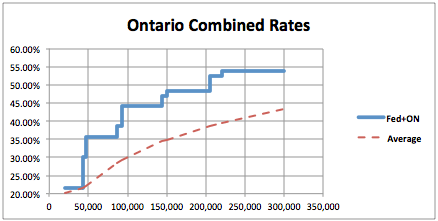

But when we say “marginal” tax rate, we typically mean marginal income tax rate. And marginal or margin means edge. So in other words, your marginal tax rate is how much tax will you pay on the very next dollar that you earn. And hence a tax “bracket” like the example above simply defines your simplified* marginal tax rate as stated by respective levels of government.

Note that this is completely different than your average income tax rate, which is the rate of how much total tax you pay on your total income. If our tax system were a purely flat tax, then these numbers would be identical. But we have a stepped or laddered or bracketed tax system, which means that you pay an increasingly higher percentage of tax as your income increases.**

* It’s going to get a little more complicated in a moment…

** Exception: For some low income earners in Ontario, there is a complicated patchwork of credits and surtaxes and all sorts of other things, so you might actually find your marginal rate decrease as your income increases, until a certain point when you move out of the low income zone, and then it follows the normal pattern.

Let’s Define “Tax”

You’d think that it would be pretty simple to define “tax”, right?

Maybe. Maybe not. Depends on your perspective.

I like to consider tax as any money that you are required to pay the government, whether federal, provincial/territorial, or municipal/county. This could include income tax, property tax, sales tax, land transfer tax, car registration/emissions test fees, health care premiums, EI (Employment Insurance), CPP (Canada Pension Plan), etc.

Fees and Premiums

On the other hand, some people will not consider certain fees as tax because you could argue that you only have to pay them if you want a service. For example, you don’t need to pay for a licence plate sticker or an emissions test if you don’t own a car. Fair enough.

The best example of this “fee is not a tax” lie, though, is back when the Ontario provincial government introduced a health care “premium” in 2004. It was billed as a premium, not a tax (just so that they could claim they didn’t break their promise of not raising taxes). But the premium was geared to income (earn more, pay a higher premium) and its calculation and payment were rolled up in your annual tax return and ongoing payroll deductions. If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck…. So, like many people, I consider that one a tax.

Same sort of thing goes for CPP and EI “contributions”. Although they are literally contributing to your future public pension and covering your backside if you’re unemployed or have a baby, they are mandatory and based on your present income, so I also consider them as tax.

Side note on CPP & EI: They max out once your annual income hits a certain point in the mid-$50k range (and they’re each different, and are even still different in some provinces). So your net effective marginal tax rate might actually decrease as your income increases above the CPP & EI thresholds.

Government Benefits

Depending on your situation, you may be eligible for several government benefits and rebates, such as GST/HST (sales tax) rebate, Canada Child Benefit, Old Age Security, etc.

These are essentially negative taxes, because you get them back from the government, and they’re connected to your income. Earn less, receive more. One could even argue that utility rebates for low-income earners falls into this category, and I think that would be a pretty strong argument.

Today’s focus on tax rates implies income tax rates. So we’ll exclude things like property taxes, sales taxes, automotive fees and the like, and focus on what pops out of our income tax return, regardless of whether it’s called a “tax” or something else creative. But it doesn’t really matter how you choose to do it, as long as you know what you’re including or excluding.

How to Calculate Your Marginal Tax Rate

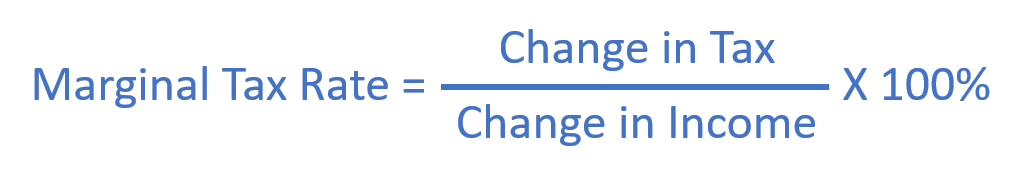

To calculate your marginal tax rate accurately, you need to play “what-if” games. So you pick a scenario (or income level or RRSP contribution amount) and record the total taxes owing. Then pick a different scenario and record the taxes owing. The difference between these represents your change in income and your change in taxes, which you plug into the equation below. This works well for changes up to around $1000 at a time.

There are probably several different methods you can use to calculate the taxes owing, but I like to focus on two, plus a bonus. If you do your own taxes with tax software, you’re in luck: The most accurate method is also one of the easiest! But if you just want some quick and dirty guestimates, or if you don’t have all of that tax info, there’s another way, too.

But I’ll start with the bonus:

Canada Child Benefit (CCB) Calculator

For anybody with kids, this is a must-do. Simply go to the link below and follow the instructions.

As you do so, you’ll have to enter your income, so you can either guess at that, or use the data from your last tax return (or tax software). Also, for info such as birth dates, you can make up any number that’s reasonable. Just remember that the CCB is less for children aged 6+, so stay on the correct side of that line for your family. You can also skip all of the optional questions if you like. But remember, the more accurate your entries, the more accurate the calculation will be.

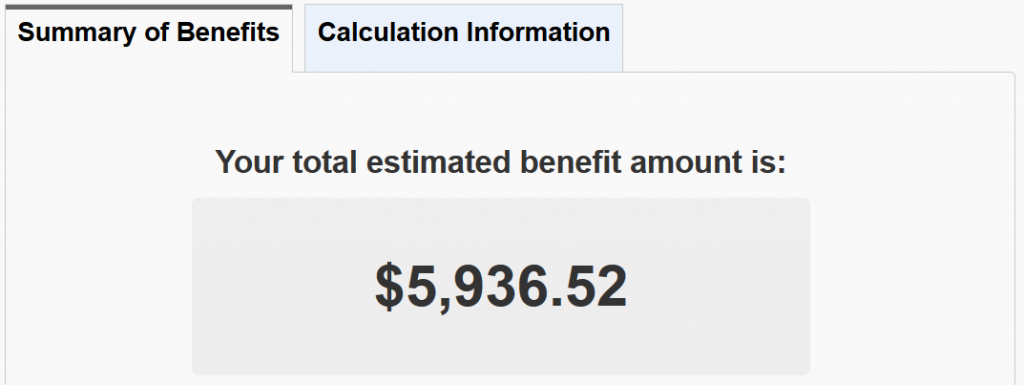

Putting in two kids aged 6+ and a total family income of $70k ($50k + $20k) yields a benefit of $5,936.52.

Changing the scenario to $71k yields a benefit of $5,879.52. That’s a benefit decrease (or reduction in negative tax, or simply “tax”) of $57.00. So, when I move on to the next step of the tax software or tax calculator, I need to remember to add in that $57 to the increased taxes, because it likely won’t be done automatically.

By the way, that whole thing took only a couple of minutes to generate, so it’s exceptionally quick once you’ve done it once or twice.

Using Your Tax Software

I like to use my tax software to play those what-if games because it’s easy and fast. It quickly gives me the total amount owing (or refunded) for our family. And I can run many scenarios quickly, record the results in a spreadsheet, and then do all of sorts of engineering-nerd optimizations and planning.

I always make sure to have two tax files, though: One for our real tax returns, and one other experimental file that starts as a “save-as” of our real tax returns. That way I don’t accidentally overwrite something important.

Then to run the games, just go to the appropriate page in the software and change the entry for earned income or whatever else you want to change. Continuing with our example above, and assuming that the total of $70k was real, exact, and based on our employer tax forms, then you would already know the tax owing as calculated by the software. Let’s say you might have a refund of $700. Write it down.

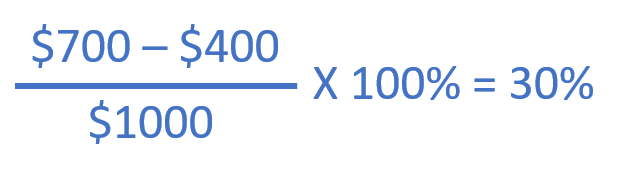

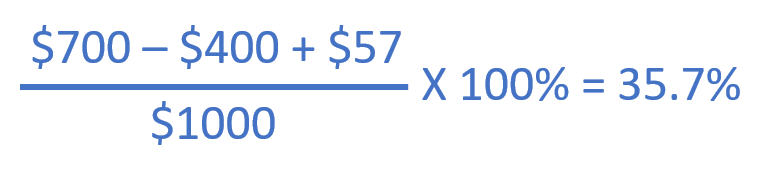

Next, go back and artificially increase one spouse’s income by $1000. Ask the software to recalculate the taxes owing. You might now only see a refund of $400. Plug all of this into the equation:

But don’t forget your decreased child tax benefit. So the results really should be:

In our scenario, you would actually have a marginal tax rate of 35.7%. Is it worth earning that $1000 to keep $643? Only you can decide.

It Works the Other Way, Too

We can also turn that example around. Assume you started with $71k and were deciding whether to deposit $1000 into an RRSP. Well, an RRSP contribution has the effect of reducing your taxable income, so you can run the exact same scenario we just did, but in reverse. Instead of paying $357 on the $1000 earned, you would receive a $357 refund on the $1000 invested. Is that worth it? Again, only you can decide.

Furthermore, depending on your tax software, it might even do the marginal tax rate for you and maybe even estimate your CCB. But you’ll probably have to look deep down in the tax return analysis section.

Using an Online Tax Calculator

You may have picked up on a key assumption in my example above: “assuming that the total of $70k was real, exact, and based on our employer tax forms, then you would already know the tax owing”. This is not always a valid assumption.

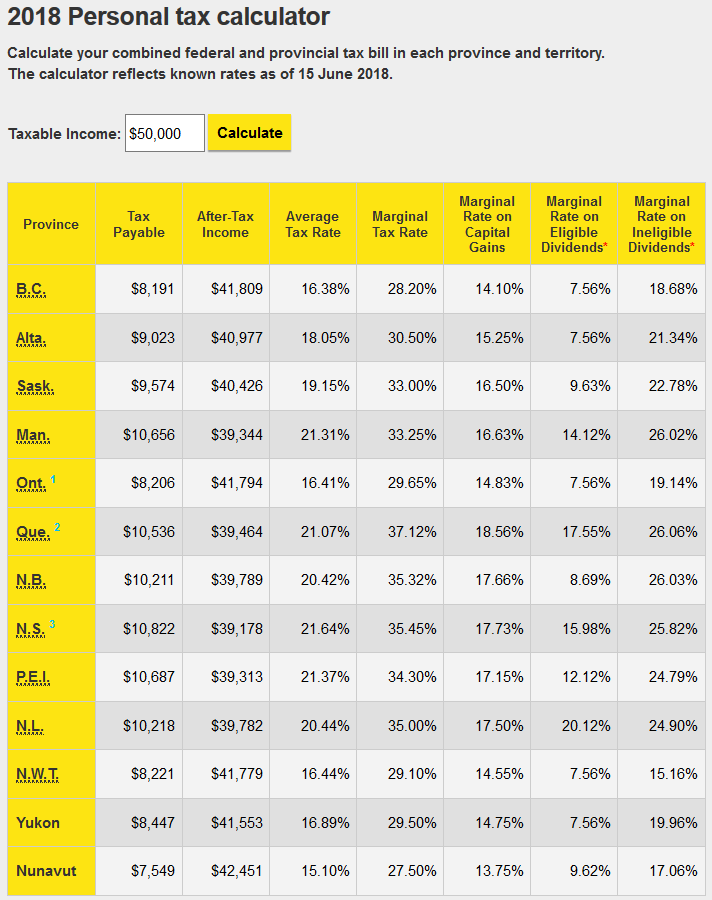

In that case, it can be helpful to use an online tax calculator. I happen to like this one from EY because it is SO simple. The internet is full of others, so find one you like. Of course, like with the CCB calculator, the more detailed and accurate the input, the more detailed and accurate the output.

https://www.ey.com/ca/en/services/tax/tax-calculators-2018-personal-tax

For example, whereas the tax software will consider tax credit transfers between family members, carry-overs from prior years, charitable donations, medical expenses, etc., the simplest of online calculators will not. Just keep that in mind when reviewing the outputs and making decisions.

The nice thing here, though, is that it actually already calculates your marginal tax rate for you. If you’re looking for a quick and dirty guesstimate, this works really well. In fact, I actually cheated and used this calculator to help build my example for this post, because I didn’t want to go and regenerate and privacy-guard all of that information for my own tax situation. Sometimes it’s OK to be lazy.

A Word on Marginal Rates for Investments

You might have also noticed that I stayed away from discussing the marginal tax rates associated with investment income. That’s because I’m not overly familiar with them, and also because I wanted to focus more on the earned income side. You can still get some pretty decent estimates, though, from the online calculators, but use your tax software for the best results.

Also worth noting is how much lower the tax rates are for investments (e.g. capital gains and dividends) than for earned income. Let that be a giant hint to you on how to accelerate your net worth growth: Shift your income sources from earned (salary, business, etc.) to investments. But that’s a post for another day!

Your Turn Now!

Your Turn Now!

I have done MTR rate calculations using the EY calculator for a couple of reasons:

1) Similar to your child tax benefit calcualtor – we used it to factor in not just the RRSP credit we would get back but whether we could maximize the child benefit we would receive

2) AS a best estimate for what our tax return would be given I have a sales role and can write off some expenses now

3) in line with the above – to get a rough idea of what my actual percent rate on the interest on our mortgage is given that a portion of the interest is tax deductible (and consequently use that to determine whether we get a better return by paying down the mortgage or keeping the money in a short term promotional interest account) – this last one I stumbled across in my head when showering and instant light-bulbs and excitement went off haha.

Hi Aravind,

I love #3 – never thought of that one! Thanks for sharing 🙂

Chris

How is mortgage interest tax deductible in Canada?

Mortgage interest on it’s own isn’t tax deductible. However if you r have some type of other business based income then you are allowed to write off a portion of your home as a home office. Depending on the type of business this can include mortgage interest.

Alternatively if you borrow to invest (ex. readvanceable mortgage or home equity line of credit) that interest is tax deductible against your taxable investment gains (interest income, dividends, capital gains etc).

Glad to help!

You’re cute.